“I started after the death of my husband—several months after. My doctor asked, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘Sometimes I watch TV or sometimes I read my holy book.’ He said, ‘Is that all?’ I said, ‘I don’t know.’ He said, ‘No, try to make something. Make crochet or something to fill your time. Don’t just sit like that and wait for your death. You have to do something.’

“So I began. I didn’t succeed with the crochet you know…” she chuckles.

And so begins a story of resilience, a story of a battered seed re-blooming into something beautiful after a long, hard winter: the story of Suhad and her art.

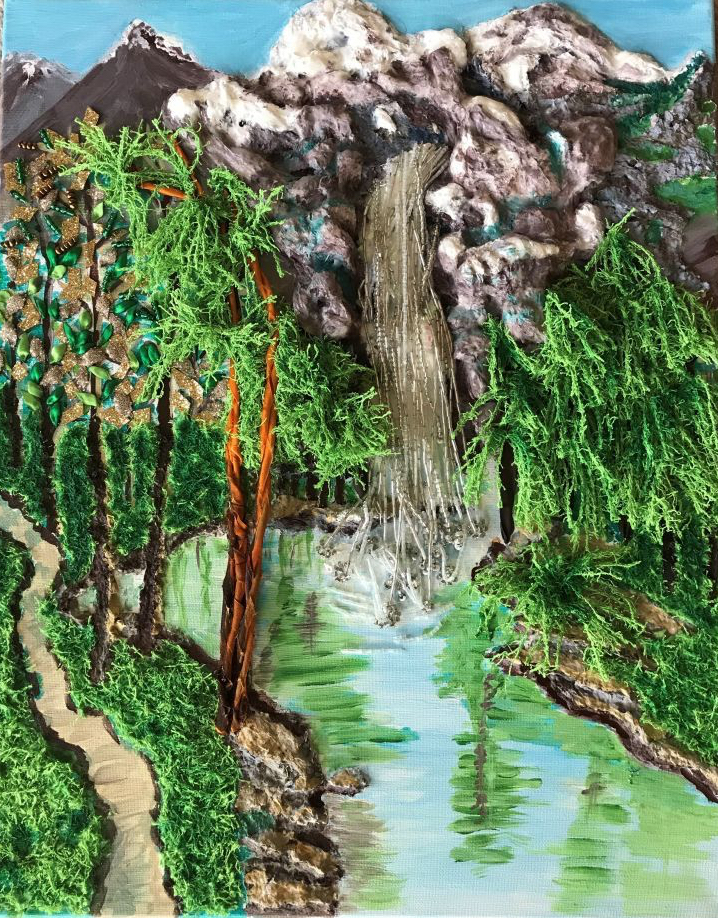

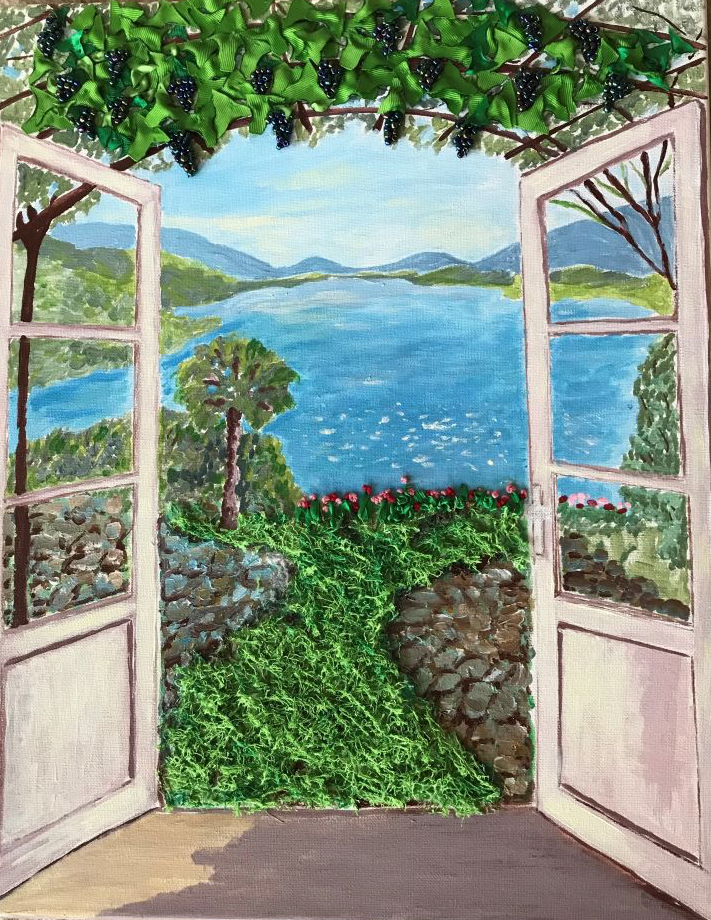

Canvases bursting with color and flowers line the walls of her apartment. Each exhibits tiny stitched-on creations of ribbons and beads on top of paint. Sequined waterfalls cascade over mountains. Roses and grapes spill over a terrace. A peacock made of jewels struts proudly. And a bicycle delivers bright bouquets.

Suhad continues, “I find myself so lonely. So this is something I can do to accomplish something.” I marvel at her humility in this room blooming with talent.

After serving tea and pastries, she settles into a stuffed chair and carefully removes her gray scarf from her long salt and pepper hair as she tells her story.

It begins years ago, before 1958, when Iraq was still a kingdom—the time that carries her best memories of home. After that, “step by step, Iraq went a little bit down down down until now,” she laments. Once a country rich with petrol and agriculture, her homeland was slowly destroyed by years of war.

Suhad learned English in fifth grade and French later on, in addition to her native Arabic. She studied in Kuwait in high school and went on to university. It was while working at Iraqi Airways that she met her husband. She is a Sunni, he a Shia—warring communities in Islam—but their families didn’t live that way. They loved each other and had a daughter and two sons.

And they had a garden–one full of roses and gardenias, oranges and lemons, mint and celery, onions and dill.

He continued to work with the Airways and she with the Ministry of Higher Education. They lived for a time in Denmark and Thailand. They were educated, productive, and happy.

But none of that was enough to protect them from the horrors of war.

As it surrounded them, their house was hit by small missiles and bullets until holes marked the walls and they were forced to live in two rooms in the back. Her youngest son was nearly killed, and her oldest daughter was at risk of being kidnapped. She and her husband made the hard decision to send their daughter to Jordan to live with an aunt in safety.

They were unable to follow, though, as Jordan’s borders closed to Iraqis. They escaped to Syria in 2007, which at that time was safe and cheap. They carried only four suitcases, having made the difficult choice of what to leave behind. She shows us a few small brass vases that she was able to carry with her when they left.

Then began the long wait.

Unable to obtain work visas, they were forced to start spending their savings. Her husband returned to sell the house they had fled only to discover it had been ransacked by neighbors four times. He sold everything that remained and rejoined the family in Syria.

Their youngest son was approved to travel to the U.S. in 2008. But Suhad waited with her husband and two other children seven more years before joining him–three in Syria and four in Jordan. They visited the UNHCR office frequently, all the while watching their money slip away as they spent it to survive.

Finally, in 2014, they were welcomed here. Her husband, who had suffered from arthritis in his knees for years, underwent two knee surgeries after they arrived. Everything went well and he was recovering.

Until the afternoon he went to take a nap and never woke up. He was only 68 years old and had suffered a heart attack.

“It was a shock for me. For the first two or three days, I’d imagine that he was traveling or something. During my prayer at dawn, I’d hear his voice—‘Suhad, Suhad, wake up.’ It’s very hard for me. Many nights I couldn’t sleep. I had so much hope that he would recover and everything would go well.”

Suhad tells how she only knew a handful of people at the time—having been here just eight months—mostly doctors and World Relief staff members, all who had helped them greatly. She speaks of Laima, her counselor at World Relief, and Kim and Madeline, friendship volunteers, who walked her through months of grief.

I ask if there are others she has met in the now four years since her arrival.

“I don’t go out. I don’t have friends. Each one of my children is busy with life. I don’t drive. This is a problem for me. I cannot drive so I have to de pend on my son and my daughter,” she laments as she waves a hand at the cane she leans on to walk. Her daughter works and her son is ill.

pend on my son and my daughter,” she laments as she waves a hand at the cane she leans on to walk. Her daughter works and her son is ill.

Here she sits, a woman highly educated and engaging, funny and able to speak three languages. She is surrounded by beautiful artwork of her own creation, a talent discovered and nurtured in her 60’s and on the heels of tragedy.

Suhad’s love of flowers reminds me that as a gardener, she knows that a seed that looks dead after a hard winter freeze carries life deep inside. She has restored that life through her talent.

Suhad’s path describes the road to recovery for many a resilient refugee:

“So I began, step by step. So I began, a little bit. I succeeded. I didn’t expect myself to succeed. I found myself so lonely. So this is what I’m making to make me feel satisfied and happy inside. I accomplished something.

“When I make the flowers, I remember my garden.”

Hope and Be.Longing

This post was also published by World Relief here. Visit their website to see how you can befriend someone like Suhad.

Leave A Comment